WIP

Protect your patients from AR

Prompt referral can improve outcomes and survival

People all across Europe are living with AR

How many people in Europe are estimated

to be living with AR?1,2

Delayed referrals for surgery can impact outcomes and reduce survival in people with aortic regurgitation (AR).3 Guidelines emphasise that patients should undergo timely referral for comprehensive evaluation before irreversible damage occurs.4 Timely referral allows patients to receive successful surgical interventions.3

of the general population are affected by AR1

are affected by AR1

are affected by aortic

stenosis (AS)1

living with AR1,2

Extrapolating to the European population means that around 3.7 million people in Europe could be living with AR.1,2

In patients aged under 65 years, AR is more common than AS (AR 0.1%–0.7% versus AS 0.02%–0.2%).1

Around 50% of people aged >65 years have at least mild undetected valvular heart disease (VHD), and the number of people with clinically significant VHD, including AR, is expected to increase considerably over the next 50 years along with an ageing population.5

The 2021 ESC/EACTS VHD guidelines emphasise that patients should undergo timely referral for comprehensive evaluation before irreversible damage occurs.4

Patients must be referred to the heart team to be assessed for surgery without delay.4

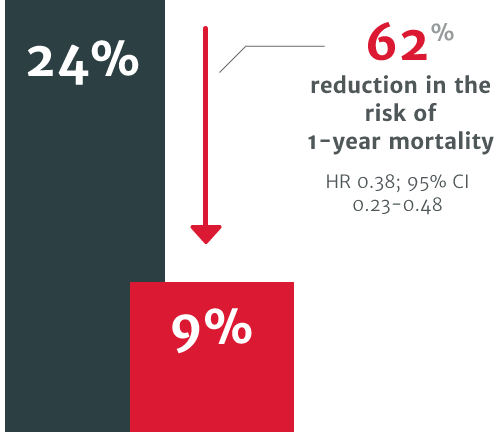

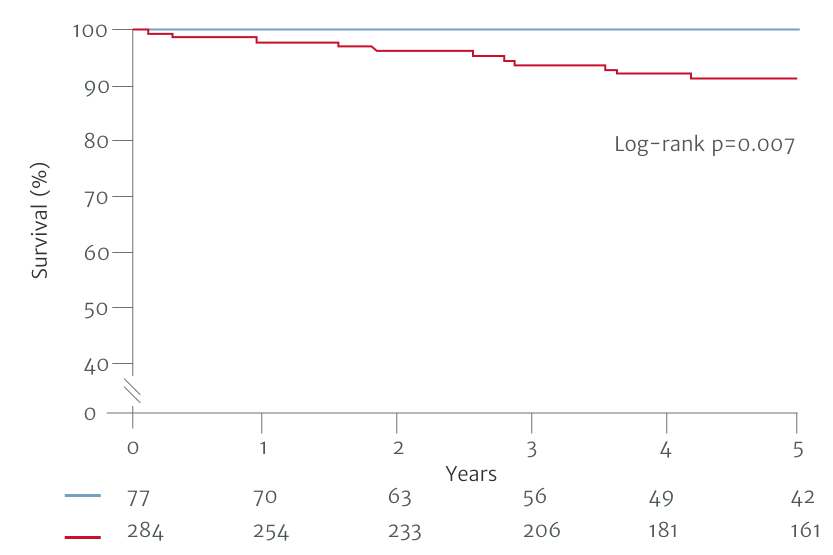

In a US retrospective study using the electronic health records of 4,608 symptomatic severe AR patients, patients who underwent surgical intervention for AR demonstrated improved survival versus patients who didn’t receive intervention.3

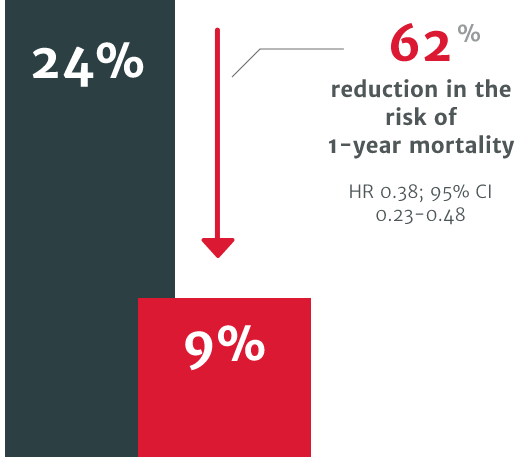

62% relative risk reduction in the risk of 1-year mortality in patients who did not undergo SAVR within 1 year of diagnosis (24% mortality) compared to those who did (9% mortality).3

WIP

Some patients are missing the opportunity for timely treatment

Early diagnosis can be challenging as obvious symptoms, such as angina and shortness of breath, usually occur after the optimal time for intervention.6,7

In patients with acquired AR, referral is sometimes delayed due to inappropriate evaluation of a patient’s severity and symptoms.8

To evaluate AR, no single measurement or Doppler parameter can be used; multiple parameters must be integrated.9 For example, to fit the criteria of severe AR according to the ESC/EACTS 2021 guidelines, evaluation includes qualitative, semiquantitative and quantitative parameters.4

Download a helpful guide explaining all the parameters used.

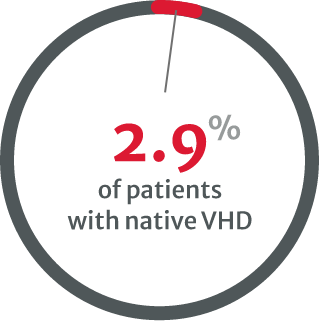

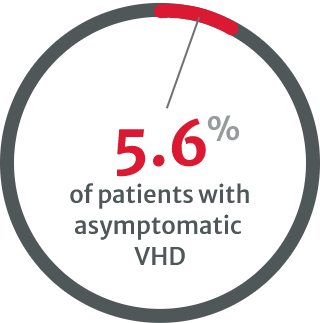

In the VHD II survey in 2017,

very few patients underwent stress testing

compared with 8.9% of patients with native VHD in 2001.8

in asymptomatic cases with severe native VHD.8

WIP

Late diagnosis can delay intervention in severe AR patients

For patients with untreated severe AR, the outlook is poor. This includes increased mortality.3

AR patients can suffer functional cardiovascular health decline.10 If treated conservatively, moderate to severe AR causes a 5-year and 10-year mortality rate of 25% and 50%, respectively.10

In moderate to severe AR patients, death usually occurs within 4 years after the onset of angina and 2 years after the onset of heart failure.10

Delayed referral could mean that patients no longer fully benefit from surgery.11

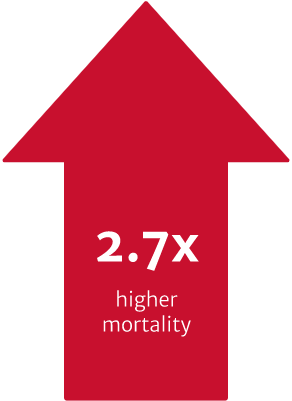

In a US retrospective study using the electronic health records of 4,608 symptomatic severe AR patients. The risk of mortality was found to be 2.7 times higher in symptomatic patients with severe AR who did not undergo surgery vs. those who received SAVR within one year of diagnosis (p<0.0001).3

In the same study, a patient’s primary cardiologist was a strong determinant of the likelihood of receiving SAVR, even after controlling for potential confounders. Cardiologists with higher SAVR rates were shown to deliver improved 1-year survival for their severe symptomatic AR patients. Addressing this variability in treatment could improve patient outcomes.3

Could earlier intervention improve survival?

The ESC/EACTS 2021 guidelines were driven by studies showing improved survival outcomes with earlier surgical intervention.6,7,12

In one study based on the 2017 ESC/EACTS VHD guidelines, 10-year survival was found to be better if AR was surgically treated before guideline defined triggers, at the asymptomatic stage (patients operated on with a Class I guideline indication, n=204; Class IIa and IIb, n=66; before guideline defined triggers, n=86).7 Another study based on a previous version of the ACC/AHA guidelines from 2014, demonstrated better postoperative outcomes in patients who underwent surgery with less severe symptoms, compared to those that waited for guideline defined triggers (patients operated on with a Class I guideline indication, n=284; Class II, n=50; before guideline defined triggers, n=27).6

Separated on the basis of Class I indications for surgery

Non-Class I Indicators for surgery

Class I Indicators for surgery

Adapted from Yang LT et al. 2019.

Adapted from Yang LT et al. 2019.

In a US retrospective study using the electronic health records of 4,608 symptomatic severe AR patients, patients who underwent surgical intervention for AR demonstrated improved survival versus patients who didn’t receive intervention.3

62% relative risk reduction in the risk of 1-year mortality in patients who did not undergo SAVR within 1 year of diagnosis (24% mortality) compared to those who did (9% mortality).3

62% relative risk reduction in the risk of 1-year mortality in patients who did not undergo SAVR within 1 year of diagnosis (24% mortality) compared to those who did (9% mortality).3

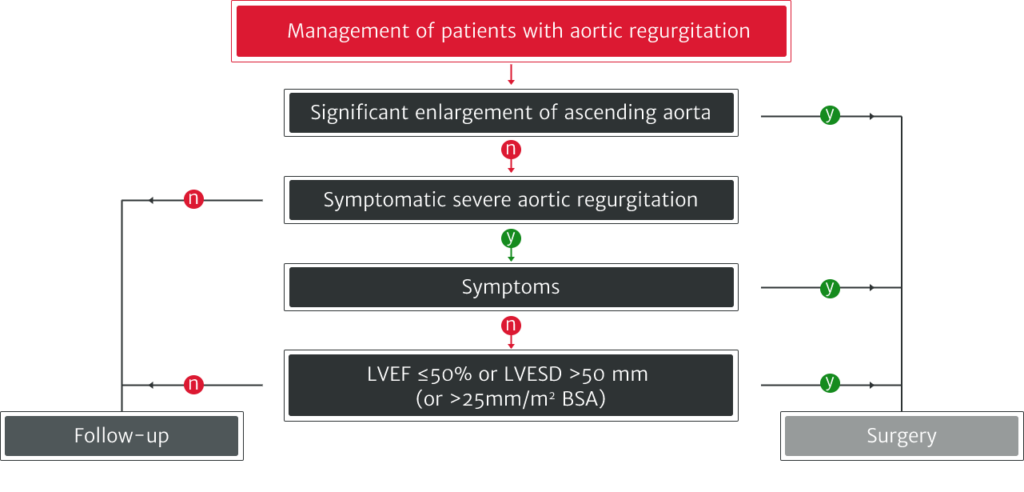

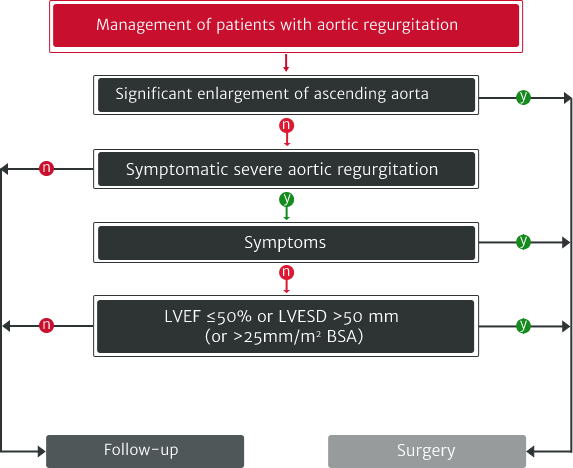

The ESC/EACTS 2021 guidelines recommend:

Adapted from Vahanian A et al. 2021.

outcomes for people with AR

Under-diagnosis in VHDs is a clear problem and may be linked to the underuse of stress testing, particularly in asymptomatic patients with severe native VHD.8 Multiple types of tests are needed, especially when physical examination and initial noninvasive testing are inconsistent.13

Further testing and regular monitoring can help to identify those who may require intervention by helping to establish the patient’s disease severity.4,13 However, the VHD II 2017 survey reported that very few asymptomatic VHD patients undergo stress testing.8

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is becoming more popular for evaluating VHD, however less than 10% of patients are analysed in this way.8

New, more sensitive markers for LV dysfunction, such as LV global longitudinal strain, are being investigated. Several reports have also evaluated the potential role of newer indices like LV-global longitudinal strain, tissue Doppler and torsion.14

WIP

The ESC/EACTS 2021 guidelines were driven by studies showing improved survival outcomes with earlier surgical intervention.6,7,12

The Edwards Lifesciences AR podcasts are a series featuring some of the most eminent cardiac experts from across Europe, with a focus on the under-diagnosis and under-treatment of aortic regurgitation. They share their thoughts on best practice and suggestions on how to improve the standard of care.

To stay up to date, don’t miss our podcast series on the definition, diagnosis and treatment of AR

When it comes to AR, don’t delay referral

don’t delay referral

View all resources

Thank you for your interest in Edwards Lifesciences

Please take a moment to confirm your contact details. Fields with asterisk are required.to receive tailored news updates relevant to you and your field.

WIP

References

1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, et al. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1005–11.

2. Worldometer. Europe population (live). 2021. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/europe-population/ [Accessed 24 March 2022].

3. Thourani V, Brennan J, Edelman J, et al. Struct Heart. 2021; 5(6): 608–18. DOI: 10.1080/24748706.2021.1988779.

4. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. Eur Heart J. 2022; 43(7): 561–632.

5. d’Arcy JL, Coffey S, Loudon MA, et al. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37: 3515–22.

6. Yang LT, Michelena HI, Scott CG, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73: 1741–52.

7. de Meester C, Gerber BL, Vancraeynest D, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019; 12: 2126–38.

8. Iung B, Delgado V, Rosenhek R, et al. Circulation. 2019; 140: 1156–69.

9. Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, et al. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017; 30: 303–71. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2017.01.007.

10. Akinseye OA, Pathak A, Ibebuogu UN. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2018; 43: 315–34.

11. Carabello BA. JACC. 2004; 44: 376–83.

12. Mentias A, Feng K, Alashi A, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68: 2144–53.

13. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021; 143: e35–71.

14. Alashi A, Mentias A, Abdallah A, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 11: 673–82.

AR, aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; EACTS, European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; LV, left ventricle/left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic diameter.

Share this page on

Edwards, Edwards Lifesciences, and the stylized E logo are trademarks or service marks of Edwards Lifesciences Corporation or its affiliates. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

©2022 Edwards Lifesciences Corporation. All rights reserved. PP–EU-4167 v2.0

Edwards Lifesciences ● Route de I’Etraz 70, 1260 Nyon, Switzerland ● edwards.com

Edwards, Edwards Lifesciences, and the stylized E logo are trademarks or service marks of Edwards Lifesciences Corporation or its affiliates. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

©2022 Edwards Lifesciences Corporation. All rights reserved. PP–EU-4167 v2.0

Edwards Lifesciences ● edwards.com

Route de I’Etraz 70, 1260 Nyon, Switzerland